Shopping with Evan Parker

London, January 4, 2002. Evan Parker suggested we should meet up at Ray's Jazz Shop ("In case anyone shows up late"). After a few hours of bracing coffee, inspiring pints and the following exclusive chat, Evan shared with us some more of his favorite shopping secrets in and around London's Seven Dials theatre district. And a charming parish church where condemned prisoners were once offered a last bowl of ale on the way to the hanging tree...

We talked about the making of Evan's new solo CD Lines Burnt In Light, London wildlife, squeaky chairs, magic crystals in the moonlight, insect field recordings, deep sea diving, marching in Nikes and voting for Levi's, Bitches' Brew, English vs. Dutch manners in music, philosophical haute couture, another little life and the age of leisure... And, of course, shopping. We started the tape recorder just as Evan was reviewing our magazine and considering our stated refusal to position ourselves as "music journalists"...

No, we don't operate like critics, that's not our attitude.

Yes, I think the magazine's flavour comes from that. That it's more philosophical. And the absence of reviews, or CD reviews...

We did write something you could almost call concert reviews... Shamelessly subjective concert reviews.

Concert responses. Reports and responses. Well, I guess there's an element of that in every review. But the notion of critic is interpreted slightly differently in different cultures anyway.

We tried putting on records and listening to them in that way. We started with some CDs a record producer had given us for that purpose. "Do you do reviews?" he asked. We hadn't thought of it. So he gave us these CDs. And we found ourselves listening in a way that was really cold-blooded and analytical, pen in hand, and the words we were supposed to be writing, really getting in the way of the direct relationship to the music.

But you do find CDs an important part of your listening experience?

The most part of our listening experience! We must have ten, twelve of your records at home, but we never heard you live before this week.

So, some other recognition of that, not in the form of reviews maybe, but somehow... Do you think that would be appropriate? Because I kind of missed it, you know? I found it interesting that it wasn't there, but I missed it.

It's true, now that you say it, someone could indeed, reading our magazine, get the impression that we never put on a record. Though we did ask Eddie (Prévost) something about the difference between the experience of a concert and the experience of listening to a record...

And he quotes Cornelius (Cardew) about looking - you can't look out of the window. Because perhaps that's the advantage of a concert. Cornelius could look out of the window. I think you can also treat records in the same way. For years I've only had a record player upstairs in my house, in the bedroom. Nothing on the ground floor, nothing in the kitchen, only one playback system. And so I can start the thing with something on, and then go downstairs, and that's it, the thing plays - like, nobody's listening to it. And at night I can play records and go to sleep.

We could write about records we listen to anyway. Not necessarily new records. How it's a part of our life. Like when we can't sleep, when the neighbors are making noise early in the morning, we put on Cecil Taylor, nice and loud. And then we're gone in ten minutes.

So, there's many ways of - you know, you don't have to sit there in the chair. In fact, in some ways your relationship is freer when you're listening to recordings. You can also say: hmm, that was interesting, what's going on there? And wind it back and listen: ah, I think that's probably the singing saw mixed up with the voice... or whatever it is. The first time you hear it, you don't quite get what it is. I find recordings very interesting, and especially CDs. There's a lot of affection for the LP, but for me - I don't miss the LP at all.

Having to turn it around, the dust, the scratches...

Yes, all of that. For me, it's such a fantastic thing that it's no longer like that. And this business that you can program, when you know after a while that you really - I mean, I listen to a lot of New Flamenco. And these records in a way have something in common with the Blue Note records of a certain period: there's always one track which is meant to be a bit more commercial.

Usually the opening track.

Quite often the opening track, but you never know. Especially compilations, or "The Best Of" and all of this. So then I know, the more it drifts toward the Gypsy Kings type of thing, which they all try for a little bit, then I know that's not so interesting. So I can program it.

We always have music on when we're writing. Miles Davis, the early seventies records, those electric jams with with a groove that goes on forever - that's great for writing.

My youngest son is listening to all that stuff again now. It's very strange for me. Exactly the period that I lost interest in Miles, that's where he starts. Perfect! You know, it's like, I can't talk to him really. He knows more than me about that area. Well, that's not the only thing he knows more than me about, he knows quite a lot of things in more detail than I do. But that's very funny, because he doesn't seem to be at all interested in what Miles was doing for the 20 or 30 years before this. So I've got all of that stuff, pretty much, I'm not fetishistic but just about pretty much all of it, you know, Birth of the Cool and Bag's Groove and Walking and all of those things that he's never asked me about - what was Miles doing before In A Silent Way? Or whatever it is, which is the cut-off point for me. I can not always recognize Bitches Brew, but there are other ones...

Oh, we love that record. It's one of the records that eventually brought us to your music.

Well, we're all different. I like it now more than I did when it came out. I must say that I appreciate that whole period of his music now more.

Maybe you were repulsed by what it represented at the time?

At the time I thought, this is real sellout stuff, this is commercialization, this is - you know, it's desperate. It comes from a pop star kind of thing.

It was also - aside from the persistent groove, which is something that can just as well be said about jazz - some of the most open, freest music he ever made.

Well, I don't know about that. I like the unofficial live recordings of the various bands. I can't remember the names of any of them... Double Moon, is there one called Double Moon? They're from various tours, European tours. It would have been before Bitches Brew. They're basically playing the Wayne Shorter tunes. So, I like that very much, and I think that was also very open form. You know, they weren't playing on the structures, the tunes, so - well, they were, and they weren't. They were doing whatever they wanted, which is great. Sometimes I get the feeling that Miles was a little bit desperate to get back to a, let's say, "whose band is this" kind of thing. I think Tony Williams must have been what we call quite a handful.

What's that squeaky sound? You got a pet mouse in your pocket or something? No, it's the woodwork, the bench... (The next minute of the recording is drowned out by the noise of the coffee machines being cleaned with high pressure vapor.) Are this kind of sounds especially interesting to you as a musician, daily life sounds?

Oh, I think I've got an ear for - maybe a bird sound, or some mysterious sound in the middle of the night. Maybe foxes. We have foxes, a lot of foxes, even in the city, because of all of those little gardens and cemeteries, the foxes find it easier to live in the city now than in the country.

Maybe because there's no fox hunting in the city! We had a very close encounter with a fox at three in the morning on Trafalgar Square...

They've moved in. And they're very relaxed, and more and more cool now. More at night of course than in the daytime. But you see them in the daytime sometimes. The later in the night, the more confident they become. It's like they're asking you: what are you doing up at this time? This is our time! And they stand there, they don't run away anymore. (The squeaking sound catches our attention again. Evan shifts back and forth to get some more signal.) Yeah, you're right, it's coming from here. Nice little squeaks.

Sounds more like a cricket now... Do you feel a kinship with the music of insects? Some of your records have been favorably compared to insect twitterings.

There's fantastic recordings from this French guy, Jean Roché, and he's for years been making recordings of bird songs from all over the world, but also sometimes insects. So there's some very good records of cicadas and crickets and... This guy started in the age of LPs, and he had various series. So some of them were edited like concerts. Some were more like classic species identification, so each track was to identify a particular species - or a survey of a particular region. And then when he liked a particular individual bird, then he would make an EP and say: this bird is a virtuoso and must be featured as an individual, this is beyond the generic or the species type, this is an individual bird with a very special - so he did a very interesting series of records, and gradually they're being transferred to CD. And also now he has younger people working, making new recordings with digital recording. It's a lot easier to do now than in the old days, going to the jungle with an analogue tape recorder.

Messiaen got a lot of his best licks from birds.

That's right. But Messiaen used to notate, directly on to manuscript paper.

He called it the voice of God.

Mmm. Big and Everywhere. But he's a little bit confined to the Catholic interpretation. But I appreciate the sentiment, yes.

God has broader interests than only the Catholic church!

Yes, I believe so!

You weren't too much infected by a religious upbringing?

Well, I wasn't given a religious upbringing really. I was allowed, or I was shown what the church was - I was taken a few times. But it wasn't obligatory. And I lived in the age of the beginnings of liberalism and the breakdown of society as it used to be known. The post-war period. All the certainties, my parents' certainties were probably destroyed by the war, like most other Europeans of their generation.

I'm not sure how many of that generation were confronting that kind of reality head-on. For most people the first twenty years or so after the war was more a period of clinging on to those crumbling values, those broken-down certainties.

Well, I'm not sure how conscious it was. You know, they were, in some ways they were like - zombies is too strong, but they were in a state of shock, everybody was. And that was precisely the age when I grew up.

So now we're free... Free to think we're all so unique and special, just like everybody else...

It's that old classic argument, that old classic statement. It depends what you mean by free, or more free. In some ways I would say they're much less free. You know, the constraints to be a good consumer now are much more - it's like, the new religion is to shop well, the new cathedrals are the supermarkets and shopping malls.

And you're a good worshipper? A good shopper?

I'm not especially a good shopper, because those places haven't got what I'm looking for!

You seemed a fairly well-known customer back there at Ray's...

I have been, in my time, a great customer of Ray's. But these days I get a lot of stuff for nothing. And I'm always doing deals, "I'll give you this if you give me that", and - so I'm not spending quite as much cash as I used to. But I did buy that new Coltrane box. It was a significant - it was essential, to have! So, to get back to your question about freer or less free... I guess in terms of conventional moralities, all of those things are now, of course, completely destroyed. People do exactly what they feel like. But what they feel like turns out to be - to go shopping. And that's not a coincidence.

And for the others? Those who try to find out a life for themselves that is not some pre-programmed soap opera? In the sixties you were either a square or you were a revolutionary. There was a herd aspect about that too.

Well, It can get very lonely. You have to share some values with somebody, otherwise there's nothing to talk about with anybody.

Or argue about!

Well, I know that the Dutch are very good arguers. They always like to take - to find a new position among themselves: "Well, if you're going to say that, then, okay, let me think about it. Oh, I'm going to say this." And then they come with another line.

For argument's sake.

For argument's sake, and for the sake of - to be an individual. It's very important in Holland that Misha is not Han and Han is not Willem and Willem is not... You know, all of these people have got their own look and their own things and their own - so we know who they are.

Whereas the English would consider such ego-posturing to be a distraction from the matter at hand? Egolessness can be a very effective political strategy too.

Well you know, then you get different kinds of music out of that. I think that you quote Cecil Taylor at one point as saying: "This is not about listening hard and responding appropriately, this is every man for himself." Do you remember quoting that? No? Well, it could be in another magazine! So, whatever music comes out of that comes that way, and music with concerns for egolessness and so on, that has a very different sound. It can be just as free, in fact you could get some people - it's context-related. The freedom is of course that since you and your response are part of the context for other people, and they have that function for you, it's very hard to unravel the knots of why anybody is doing what they do in a given context. I think it's pretty clear that you could sort of go with the flow, or you could go against the flow. And sometimes what the music really needs is for you to go with the flow, and sometimes what it really needs is for you to do something different. Or anybody, somebody, to do something different. So that's why people improvise, presumably, because they want the freedom to behave in accordance with their response to the situations. But since their response then becomes part of the new situation for the other players, it's very hard to say why a particular sequence of events unfolds in the way it does. But we get used to following the narrative of improvisational discourse...

Like any other form of communication or collaborative effort...

It can be compared with almost anything. There's almost certainly somebody who's done something in some improvisation somewhere, you know, that's pretty much like anything you can imagine. Like a machine or like a tree or like a physical process, like a cosmology or... It depends on the imagination. John Stevens was always very keen on trees. Nowadays we all know about fractals in nature and all of that. I think that was something that John was quite responsive to, the idea that there was detail at every level. So you could look at the landscape, or then you could look at the tree, or then you could look at the leaf, and then you can take a microscope out... And at every level there is detail that's just beyond what you can focus clearly on. That's it. I mean, to try to have that, in improvisation, to have that quality as well - this is quite a challenge.

For your latest solo CD, you chose to record this in a specific live environment, at a specific time and place - as opposed to going into a professional sterile studio where you have all the parameters under control.

Well, it's strange that you should ask that, because I had about five hours of studio recordings leading up to this record, five hours of solo material specifically for the next solo CD. But then, each time I went back it was different, a little different from the time before. And I realized what I need, in the end, especially with the solo recordings, but maybe with any recording, is a sense of a very specific time window, time frame. And that was what was missing. And I couldn't - I'd take this piece from there, re-sequencing, and in the end I got lost in it. And especially with the evolution of technique that was happening at the same time - after about two years of working on this project, I thought, well, I can do all of this better now than I did then. And what's the point of putting out tapes which are - however good they are, but at this point they're three, four years old, some of them. And so I just put everything back in the drawer, and then went to the church and recorded it again.

In one day.

One day, one piece before the audience arrived, two pieces in the concert context, and that was it. And accept everything with that. No editing, no omissions, everything I played is there. Well, everything I played solo is there. And that then seems to me about as honest as you can be, and that's what I wanted. Of course now you can say: yeah, but what about the five hours that you threw in the drawer?

Maybe you needed to go through that before you were ready for the other situation?

It's true. The biggest editing you can do of all is to leave - you know, to decide to do something now, and not all those other times you tried. But records should be the best you can do, and you should feel happy about it. They shouldn't just be average, they should be your best, I think. And at the same time, I'm not sure what would have happened if I'd been unhappy with the way I played. But the truth is that I made the decision before I listened back.

Recording live certainly strips the process down to its essentials.

People like that sense of occasion, that it's played for an audience, however small the audience is. There is more focus to the listener. And in the studio you can get lost in a kind of idea world and there's no sense of - who is this for? This is actually for somebody to listen to, whether they love it or hate it.

Do you think musicians might be more conservative onstage than in a studio, especially in their own home studio, where you will maybe try things that you don't know if they're going to work - whereas onstage you want it to work, so you might not be so willing to take as many chances?

Probably true. And different places produce different, slightly different risk levels, degrees and types of risk. The recording with Han is a studio recording, in the same studio where I tried all these solo things. But with Han we just went, played, and that's it.

An audience and its expectations can also be distracting. Studio records often have a sense of warmth and intimacy among the musicians, of friends among themselves, sealed off from the pressures of the outside world...

Yes. All I can say is that if a group is going to continue to record, make more than one record, that my preference is for one element live, one element studio... In a live situation - unless you plan it in a particular way, so the groups are alternating or whatever - you play the whole music, or substantial parts of the music, in one set. Whereas, when you make a studio recording, you might play a piece, go into the control room, listen back, think about what that piece is, what does it need next. So you might get more of a sense of a slightly controlled form coming out of the studio recording. Or you have more ways of intervening at the formal level, making decisions that will impact on the final form of the pieces and the way they're sequenced and so on. But I think it's pretty much - it's not absolutely a legal requirement, but musicians very often seem to like to have the pieces on the record in the order that they were played. There seems to be something about the narrative of the individual pieces which connects those pieces together in a particular way. Like I say, it's not a legal necessity, but - I prefer wherever possible. And maybe you'll drop a piece, or maybe you've gone slightly too long, you don't realize that the session's finished. That's a quite common thing, is that you don't realize that you'd stopped playing about two pieces before you stopped recording. And the last two pieces were just using up the time, or - you've done it, and that's it, and it ended some time before you realized that it had ended.

This is a hard one - no, hard for us, to ask! Truth, spirituality, whatever you call it, or don't call it, is easier to address through the abstraction of music, than through words. It's so easy to end up sounding like - you know, magic crystals in the moonlight...

Magic crystals in the moonlight! Hello, all right! Okay, I'm all right with all of that.

It seems especially some European musicians will go to considerable lengths to avoid explicit references to spirituality. But for you it's not a dirty word?

Not at all. I find the universe to be an amazing place. The idea - like we said, the problem with the Catholic view of God is that it's too proprietorial. I like to believe that the really inspired or - what would the word be? The truly enlightened people from all those religions can talk together and they - there can only be one truth. You can't have the truth be the exclusive domain of this religion and not that religion. Because if they're telling the truth, they're all at some point saying the same thing. And I believe that that's the kind of spirituality that I'm interested in - is where there is a core of it that must be the truth. And the truth must be about the miraculous nature of the universe that we're born into. And our opportunities to learn and develop and to understand more are built into the way the universe is structured. And you can call that spiritual, or, I don't know, you can call it scientific, or you can call it philosophical. But at a certain point, if a philosophy is telling the truth, it's saying the same thing as a religion - if a religion is telling the truth. And if a science is telling the truth then it's saying the same thing as a philosophy or a religion. An understanding, an insight can come through any of those disciplines. But at a certain point, if it's saying something true, then it's saying something universal. That might be a spiritual idea.

What about the fashionable relativist idea that there is no one truth, but an infinity of subjective, completely different truths, so you can never really communicate about truth - that everything is true so that in the end nothing is true?

These ideas come from people that deal a lot with languages. Language-based philosophers especially come up with these kind of ideas. And I think what we find attractive about music is that it's not language-based in that same way. It seems to be able to talk about things in a more general way, but at the same time in a more specific way sometimes, than philosophical language can cope with. I think you can do anything with words, you can play around with words and paradoxes and the various language philosophies... Okay, it's a great way to pass the time, it's a great way to see if your students can keep up. But it's about playing with ideas. It's about playing, in the same way that we like to play. You play with ideas, and you play with the notion of intelligibility and complexity, of how far you can complexify a system of thought and still be intelligible. Some of that stuff is on the limits of intelligibility, and a lot of times requires that you learn specific terminologies, and that can take a long time. But that's a perfect thing if you're a student - perfect sort of material for a teacher-student relationship. The terminology is complex, it takes a long time to learn. You may not actually be saying very much in the end, but by the time you've come to the end of that you've got your degree. And the teacher has moved on to another level of complexification, or there's a new generation of people that are saying: yes, that was okay for its time, but now we don't really see it quite like that anymore. It's playful, I think. And for me, it relates very much to the idea of haute couture. It's for me not at all surprising that the post-structuralisms of various kinds, they're like couturiers who come with - skirts will be short, or skirts will be long, or feathers will be worn or feathers won't be worn, or fur is in or fur is out... Same thing, you have to know the context in order to understand the references and understand the sequence in which one idea supersedes, or is said to supersede, another. And in the end it doesn't really - why is a short skirt better than a long skirt? Maybe because we're bored with long skirts and we want short skirts, but why, why, why? It drives the market brilliantly as well, because the more extreme - for people who are really determined to be fashionable, it must drive them crazy, you know, that they just spent 600 or 1000 quid on a suit, and next year it looks ridiculous. It's a bit the same, for me, some of those philosophical trends.

And musical trends?

But you see that improvised music is rather resistant to those trends. And I don't want to sound superior or anything like that, but it's just how it is. It's just that we're attracted to something that is a little more stable, that is not looking for a fresh packaging all the time. You know that thing they said about - that rats can live more easily off the boxes the corn flakes come in than from the corn flakes themselves? There's more nutrition in the cardboard! I don't know if that's true. But the container and the content thing is something that - I think we're quite easily able to distinguish between the packaging and what's inside. And once again, we're back to shopping. But let's hope that we're in the vanguard of more serious shopping.

Let's hope that we never become reduced to a product or a fashion you can shop for.

You see among even the well-meaning... Some of the photographs of the protests in Seattle and Genoa, you see the protesters wearing Nike logos on their - it's like, yes, it's good that you're there, but maybe could you think a little bit more about your footwear? Not that it's easy for any of us to be doing the right thing. I noticed that the shoes that I bought this time - I always try to buy the same thing, and now I realize for the first time they're made in China, but you only find that out once you've bought them. I was trying to buy the same thing that I've always bought, and now it's obviously cheaper to - and this is what's driving the shopping. This is what makes us all rich as shoppers in the Western, so-called developed democracies. We're shopping for goods that are produced by slaves.

And now, with the economic squeeze and the "War on Terror", we're being told, especially in America they're being told, that it's your patriotic duty as a citizen of the Free World to go on shopping - the indisputable logic being, if we all recoiled in a state of shock and stopped spending, the economy would collapse, which would mean victory for the terrorists. So to win the "War on Terror", we have to go on shopping.

Yeah, there were one or two quite honest things got said.

In other words, carry on like nothing happened.

I don't consider myself capable of putting the best arguments for this stuff, but there's something about globalization and the way the International Monetary Fund works, the World Bank and all of these things, Third World debt, the way the whole thing is knotted up together - it needs to be broken. It's a chain, it's a knot, and somehow it needs to be cut. It would be good if countries could think about self-sufficiency. But I don't know how. The whole shopping lifestyle - you know, feeling good is about shopping well, for most people. And shopping well is a statement about the fact that you can afford to spend at a certain level, and if you can't buy the real Nike, then maybe people won't notice that it's a fake Nike. Or maybe you can buy some fake Levis that are so good that people won't know that you're wearing fake Levis. You know? These are the options for us as shoppers. And a lot of energy is being spent on those kind of decisions which in the end don't mean very much. There are more important things to be thinking about.

Most of us end up being completely defined by decisions that we made, or other people made for us, a long time ago. Decisions like having a family or a business, creating obligations that completely regulate our lives, that put us into the hands of outside restraints, that make it almost impossible to go on making individual decisions, to go on living according to our own values and aesthetics...

Whether you like it or not, there are elements of your life that are pretty much fixed and beyond your control. And however much you would like to be free in your dealings with that stuff, you come up against those fixed elements. So I think it's a question of seeing where you can stay creative and where it would be a waste of energy to worry about some things. A professional life in this music, which I have - I don't have any other way of making a living. This is what I do, and it's what I've always done. There are constraints on my freedom in that sense, but they're ones which I trade off for that moment where I'm in the other world. And then nobody can constrain my freedom. But to get to that point you have to accept there are those channels, ways, groups, patterns of behavior which you probably have to have a relationship with. And probably the same applies to you, however much you try to live in a free way that reflects your aesthetics and your philosophy.

How can a musician play freer than he is? To us, art and life are one. It's not a separate world. The art should be a product of the life, and a source of creation that fuels creativity in the "real" world as well. The same values should apply. Or at least we should go down trying! But for many musicians, some of them great musicians - it's sad to say, but when they're not making free music, they're living a very un-free life which is not very different from that of their neighbors.

I think you've identified a very interesting - musicians don't seem to be so good at that. The place of the music is an idealized place, a utopia in that sense. And nothing you do about the way your life is organized can ever get to that utopian nature that you discovered and experienced when the music's really working well. So, people may just give up on that. They may just say: it's hopeless.

But improvisation is more than a musical idiom, or a time off from reality... it's a way of relating to the world, a state of consciousness... Isn't it?

I've already mentioned John Stevens once, I'll mention him again now. He talks about the music as being another little life. Another little life. And when I close my eyes, that's the life I'm in. That's where I'm in that other life where I'm not shopping, not in that same way. I'm not disappointing somebody by not spending the right amount of money on the right thing. I'm in a place where shopping is not done. For the moment. Because it's only a small life...

Why call it small?

Well, reduced. Because you don't need to eat in that life, you don't need to pay the rent in that life. You're shut off from those so-called realities. Then you are in another place, you are in another universe actually. That's like time travel. There's miraculous aspects to it. I've lived there a good part of my life. Like you spend a third of your life sleeping - well, I've spent whatever proportion it is in that other place. I've spent a lot of time there. And of course, it becomes harder and harder to - you kind of decompress when you come back. It's like a deep-sea diver maybe, you come back with a lot of danger of nitrogen in your blood, and if you come up too fast and - this is sometimes hard. It's good that you didn't want to speak up too much after we finished playing. This is often a difficult time. And that's the attraction of it. You become disappointed with the way things are, you become - pessimistic is the wrong word, but you can't see any way through. What is going to change about all of this when you have all these forces saying that this is the end of history, this is the new world order, that's how it is, now go out and shop. You vote once every five years and the rest of the time you shop. Every time you shop is a new chance to vote. But you can only vote for three different kinds of Levis or whatever.

Do you have a certain kind of methods to reach that place, besides the music itself? Or do you just put the horn in your mouth and it's there?

Pretty much. I think it's like people that go into clairvoyant states. The more you do it - you become used to hypnotic states. And you become adept at switching backwards and forwards. Probably the comparison with the problems of deep-sea diving is not quite right. It's a bit more like a being a dolphin, that you can go down and you can come up in a shorter space of time than someone who's not used to doing that. But nevertheless, there still is a kind of problem of transition from one space to the other.

Your music never seems agitated or restless. Even when there's a lot going on, you always sound very - well, peaceful.

That's very nice. Thank you. If you see it like that, then I'm pleased, because that's how I feel.

That's also how it looks. Your fingers and your cheeks move a bit and that's it. Whereas, a lot of sax players especially, make a lot of - they grimace and grunt and thrash about while they play, which suggests emotional tension and release.

There's that feeling that music expresses pain. This goes back the idea of the blues...

The tortured-soul-crying-out bit.

I don't know that it's like that for many of the musicians. More like a feeling of: ah! Here's a place where I can be myself, here's a place where I can do anything. Here's a place where - it's more ecstatic. Thurston Moore has that label called Ecstatic Peace, making one-sided LPs of screaming saxophone players. Very nice idea.

There just might be a future for this music.

It's unstoppable. It's a force that seems to be needed. Maybe it has something to do with a antidote to this - the other thing.

Do you think it's easier for the younger generation of musicians to step into the tradition that you've created, than it was for you to set up that tradition in an unsympathetic environment?

When I started we had a welfare state, the rents were cheap, food was cheap. Anybody who starts now, they've solved a whole set of problems that I've never had to solve.

So you're saying it's actually harder for them?

Much harder. It represents more of a leap in the unknown for them than it did for me. Once their student days are behind them, maybe there's a huge debt to pay off, which wouldn't have been in my days, the rents are like I said sky-high... The practical problems that they have to solve, to exist, just on a week-to-week basis, are so much more complicated. I thought that the way things were going - in fact, I was taught at university, what you have to prepare for now is the age of leisure. This is what we were told, as students. We had special classes about preparing for the 20 hour week...

Which never happened...

Because then what did they do? They made a decision that some people would work 80 hours and some people would be unemployed. That's the way it is now. That's not what I was promised. I could complain about it if I wanted to! I was promised an age of leisure. The problem for my generation was, what are we going to do with all this spare time?

Monastery photo galleries:

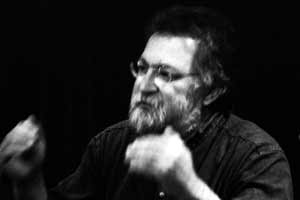

Evan Parker:

Paradox, Tilburg, Netherlands, January 2002.

(19 pictures)

The 2001 solo CD Lines Burnt in Light is available on

Evan Parker's own Psi Records (www.emanemdisc.com/psi.html)

(opens in a new tab or window)

All words and images copyright 2002 by Vanita & Johanna Monk