The Birth Cry Of A New Flute

Photo by Jacek Futiakiewicz

Love for music is not a hereditary quality. We can testify to that. And what about improvised sound art? After last week's family-audience premiere, we found ourselves hosting an impromptu barroom forum: creative music in the rumpus room. But the beer-can player knew better. Didn't we get it yet? No matter what the audience is up to, everything you hear in the venue during the concert is part of the performance. It's easy for him to talk, up there on the stage, submerged in the music. Of course we were aware of the theory. Like communism, a nice idea, if only people weren't people. As a composer you can make the band play nothing but rests while the audience sits listening to their own breath or the ambulances raging by. The everyday sonic wallpaper, transformed once again into a mystery. And not only is every passing noise Art, it carries your signature too...

Unfortunately, there are other possibilities. Like classical music, it all depends on the interpretation. We wouldn't even mention the tenor's dog. A wet nose, oozing under our seats, licking its way up our fingers. Begone, you lowly beast, you worm! Have you no shame? There's no rest for the meek. Grovel, squirm your way to center stage, to the eye of the cyclone, where you can see the noise coming. Cower and flinch to shrill attacks, even before they hit you. At least it kept its mouth shut.

No, the real trouble, as usual, is humans. Little children enjoy noise only when they can make it themselves. And the parents? No use trying to talk sense into them. They know their menagerie is on its best behavior. The price for the listeners among us is high... Daddy tella story you sweeta be. Kiddie candied honey sugared. Notta run notta fun. Basso continuo lost in wrong concert. Kills the quiet what?

Photo by Jacek Futiakiewicz

Then you got the lively young grandmothers. In need of a need to be needed. Maintaining the family snapshot archive isn't a hobby, it's a vocation. For this no inconvenience is too great. Flash. Noisy automatic winder. Still, two heads are better than one. One to take the snapshots, the other to explain before each picture how to operate the button. The audience tonight is one big family. No telling whose though. When a family member climbs on a box to make noise with a self-made instrument, you don't listen or think. You just beat the meat of your hands.

Meanwhile. Onstage. We see it all come together. For weeks they've been building their noise machines, learning to make them sing. Knowing it's there, seeing it take shape, wondering how the dream will sound in space. Then it happens. It doesn't always happen. Should it? Naked is dangerous. Alertness, a quality of listening. You could fall through the ice. Breathe in a chest full of frozen water. Or just slip off into the mud. What is will never come again and every heartbeat counts. We're listening like it's our own bloodstream.

The group clarinet doesn't sound group but desolate hollow mountain. Their voice howls inside you and wakes up the void. Blackground for shrieks of metal on dry grindstone. Crescendo of orchestrated chaos. We're not buried yet - we be. Against the chronic pressure of everything dead and normal. Then they restrain and life clenches into a whisper. Like sparrows fall silent. Don't know why. All together on a hot afternoon. Silenced sounds, loud as a knife. Grass breathes audible. Reeds breathe, signal, the next scream, even noisier, no way in this thick heat to attack without warning.

Amateurs in the best sense of the word are lovers. They have their own audiences. Connoisseurs usually stay at home. But justice will be done, and soon, and we will be there to witness. The Rotterdamse Improvisatie Poel (R:IP) are performing their Refinery at a real jazz festival in Eindhoven and we're on the bus.

***

While all the hardy men and women unload the gear, Vanita strolls aimlessly into the concert hall. A tall black cat with dreads sticking out under his puffy cap is leaning against a loudspeaker, smoking a menthol cigarette. "So, and what are you doing here?"

She doesn't take back her gaze. She's looking for the myth, behind his eyes, a mile or a minute of the light years of sound infinity spheres Sun Ra bequeathed his band. He must be one of them. Trained in detachment, no ladies, eighteen hours a day of rehearsals before and after the gig. Discipline, that's what it was all about according to the master.

"Just being beautiful... Good for nothing..." He laughs with open teeth: "The best things in life are useless!" The conversation orbits elliptically from her leathers and furs to his few years with the leader, now forever incorporated into outer space. Around them, the rest of the now posthumous big band carries all the chests and satchels full of music to the stage.

In the dressing room our band's personal chef has already set up positions - he won't be cooking today, still he's got everything under control: he uncorks, pours, and knows right away how to locate the tiniest sugar cube, what's with and without meat and where to find it. One of the Americans sees that we've got coffee and they, in the other dressing room, don't. Our chef, who never has enough musicians under his jurisdiction, not only shows him their coffee material but goes on watching over them like a grumpy old guardian angel.

The meat dishes are served only in the Afro-American dressing room, while us honkies from both sides of the ocean are provided with a vegetarian meal. No explanation for this. Nobody crosses the line.

Audiences are used to waiting for the band to show up. It's part of the ritual. Anyone wishing to experience some serious waiting, should spend a day or so with the musicians themselves. Waiting for transportation, for the sound check, for food. Hanging around backstage waiting for the gig to start. You begin to understand why so many creative musicians got hooked on boredom-killing drugs. Because there's not enough time for anything, and too much time for nothing. You'd like to talk about the music. Where it's leading us. You can share a nod of recognition, transfer some signals, like ants meeting far away from the working hole. That's about it.

What band are we with? What instrument do we play? Are we the roadies or the groupies? No, we're here to write. Not about the music - we don't know anything about that - but about what happens to us when we listen to it. "Write? For what publication?" Because a writer is someone who publishes, everyone knows that. We only write, so we can't be writers.

Brandon Evans, who will be performing first tonight, asks us to send him a copy in New York. Our first reader. We're standing outside because he thinks he's doing something pungently illegal. He has to get rid of all his grass before his plane takes off, so he's continuously rolling new joints that never come back his way.

"Do you know Martin van Duynhoven?" he inquires. Of course. Middelburg, Festival Nieuwe Muziek. Brash drums filling front stage. Four kits, four men, sixteen limbs beating clockwork. Horns and stuff in the back. Sharp, precise frame with pricked ears, surprised greyhound snout, sticking out of his smart white turtleneck and checkered jacket like it doesn't know any better. Or Rotterdam, Dodorama, a few years later. After the gig his poor neck is stiff, can't unwind. Vanita offers to rub it, but he stays every inch a gentleman: better to suffer in silence than to be fondled in public, even if it's just the back of your head.

After the sound check we hear Martin talk shop with Han Bennink, evaluating the merits of the complimentary house kit. "When you look at it you think, no way. But it's not that bad really. Better than setting up all your own stuff anyway. Han, all you got to do is stick on a couple of your whatnots..." Like two boys on a desert island, a hundred years of adventures they've survived, that's how they laugh together. One is disguised as a gentleman and the other as a peasant and that's the way they play jazz too. The bottle is going round again. This is the school trip that would have changed our whole life.

Strangers In The Night

Brandon Evans and Martin van Duynhoven have never met or even heard each other's music until the sound check this afternoon. A festival promoter - basically, anyone with the gastric tenacity for a day gig of sniffing down the pork barrels and cleaning up the leftover paperwork - actually has this power to become a part of the creative process. It's not called "programming" for nothing. The hungry artist usually takes whatever gig he can get.

Creative musicians are generally starving, not just in the economic sense. Cats getting written up in throwaway pamphlets like this one more often than they get a paid gig. It used to be worse. Now at least there's nobody trying to shark you since everyone knows you're never going to be making any money anyway. So the promoters must all be dedicated fans. We hope.

Brandon studied with Chicago composer, horn-eating reedman and Professor of Music Anthony Braxton, and he plays five different horns on "Tentet (New York) 1996" - a radical new step in Professor Braxton's lifelong research into non-narrative, constructional strategies of composition and improvisation. Here, the preconceived and the extemporaneous are entirely determined, not to say swallowed up, by the same shifting cyclic patterns, the one-beat staccato drone of the Ghost Trance Musics: "A main clean flip in the megamusic songwave cycle as evidence in each new note each repeated string of maintenance of and reference to (a reverence to) the structure..." (from the liner notes by Steve Dalachinsky).

Brandon's music tonight is also about cycles, repeated strings and structures, tunes without a melody, static improvisations. Not to mention hypnotic syntax. Trance. Clarity through confusion. Thrill through repetition. Concentration through sleep. The colors haven't changed since Chicago in the sixties: contrabass sarrusophones, piccolo tubas and other cumbersome, unplayable-looking horns. It takes Brandon and his instruments a few minutes to warm up to each other. Happiness is a wet warm horn. A big, glorious tone. Round and round the earth. Cyclic music is most effective when the performer doesn't breathe during the performance. The short night and the long wait, and now this ghost trance, inaudibly subtle shifts in endless flurries of tiny notes... Martin could probably feed any composer instant counterpoint straight off the lead sheet. Keeping timelessness. Pas de deux for centipedes, arranged by coincidence. No sorting out which feet are holding hands and which are doing the steps. They could get tangled up, slip off into abyss of banality. But they're old hands. Walk in night city, one plays blind, the other leads.. Heading for what. As long as it's dark. Stray forever in world without anything tangible.. Except the leading hand and the place where foot soles touch the earth.. Stroll in an empty universe. Wherever you step something solid rises to meet your foot. Sounds move around you. You don't hear a car but a displacement of air. Voices faint along. The drum of heels. You're still not falling, you balance yourself on the sounds. Not lifting you up not letting you down, just going on, into the depth, in the emptiness. Leading to nothing, always giving you a step to go nowhere. Applause opens our eyes.

After the gig Brandon shows us the score. How does he find his way through this maze, grass or no grass? Busy complex lines on staves that move up and down and swirl across the page and converge into each other. Straight notes, but without any clefs or signatures. Is it in any particular key? "No, it's just intervals, you can play the melodies in any key or register, of course all the flats and sharps change then but you can fill that in as you go..." Piece of cake.

***

At last it's time for our travelling companions to show the world what they're made of. In this case, junk. But, as the Buddha said, out of the mud grows the thousand-petaled lotus. Usually the R:IP plays on musical instruments. The idea of this project was to play on something else for a change. How to prepare for freedom? By practicing scales and changes all week? Sowing seeds on polished marble? The problem with good instruments is they're made to play straight. Why not create an instrumental environment where legitimate technique is irrelevant, even impossible? Hence de Raffinaderij: the Refinery.

They swarm out over the stage, plug themselves in to their secret instruments, solemnly casual, like they've invoked a ritual and are waiting for the spirits to show up. The spirits don't let them down. Battery of wild reeds, rattling drums, rumble pipes, decaying fanfare. Search party of archaic life forms. Arm length of bamboo with tenor mouthpiece wails first solo of creation.

Photo by Katja Vetter

The Raffinaderij itself is a giant multiple-player clarinet made of plastic sewer piping, plastic soft drink bottles and flexible tubing, mounted on three bar stool frames. The air supply is provided by two bicycle-pumping musicians, and regulated by a valve-and-balloon operator. The pumping seems to have some effect on the tone and pitch, though most of the actual musical decisions are made by the other players - sometimes five at a time - who open and shut the holes (using plugs, hands, rubber gloves with a tuned reed at the tip of each finger), knead the air and sing and moan into the instrument.

Zither of scrap sheet metal and scrap metal strings strategically electrified - microkinetic bowing with rusty screw. Saxman plugs mouthpiece into slide kitchen plumbing left over from improving home. Guest keyboard virtuoso unleashes his hammers on violin racked face-down. Keyolin is the name of this violin bondage. Violin responds in subdued tones, tonal tones. So does the daxophone, or dachsophon, borrowed from German guitarist-inventor Hans Reichel. It's been described as a cross between a violin and a xylophone. Looks simpler than it sounds. Small blade of polished wood, a violin bow, contact amplification, optionally a curved wooden block with frets down the back can be applied for pitch control. Less tuneful is a "squeaky grinding disk" that hasn't seen anything sharp in decades. Chair leg used as striking/bowing device is no exception. Refining is fine, as long as it's never finally refined.

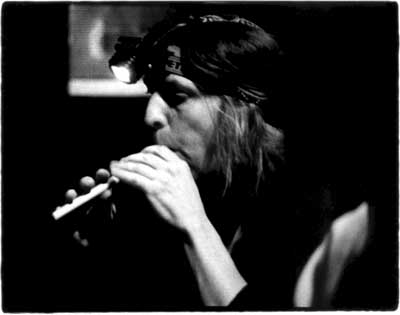

The inventor (our cover girl Katja Vetter) of the mother monster clarinet crawls into an old school desk, fixes a miner's lamp to her head, illuminates the void with a soundless solo of smoke, knives, chisels and sandpaper before standing up to blow the birth cry of a new flute.

Be aware, me of mine, open your hidden ears. The cartilage construction on your head serves even while sleeping. But what do you hear except your own noisy filling? Like I spoke to me as a child. This very moment. Be alert. Once the movie will end. Daily life again. Watch the wall around the screen too. Bring time back. Not just a flash of delight. Not get lost in it. Not miss any breath. This will expire. Must remember right now. Skying friends. Fear of height. Hums in the dark and murmurs at night. Get back wicked demons. Not too scary, not yet, but they might unfold. Voices crack, scream unrestrained, blare sonorous. This game is no game. Snake awakes in basket. Gets blows to rise. Elevates twisting. Hangs in the air, caught in serpent tunes. Sound stubbornly refuses to grow music. This is a dance to burn comfort, to find the untamed music that's hidden in the howl of the matter.

Photo by Jacek Futiakiewicz

To save us from getting entirely carried away, there's a touch of the mundane too, a glimpse of the process... oh boy. "Well, maybe... Yeah, but... You know, still... I dunno... Uuhhh..." Just to remind us of the abject forms of communication we resort to in the absence of music. Interspersed intermezzos of tone deaf mumbling, recorded from the workshop floor. Could better have stayed there.

All the kneading fingers, inflated gloves and windy mouths drop out one by one, and the undoctored naked belch of the Raffinaderij shines through - and a beastly sound it is, fat and hollow and gross and cheap like the industrial plastic it's made of. For a second they all stand there looking at each other like the coyote realizing he's way past the edge of the cliff, poking his toenails at the abyss under him.

But the voices swell up and the singer steps forward and his voice and his eyes search the black heavens for the giant heart blimp red full and pumping brute love noise into our senses. The inventor bursts the air-regulating balloon. The silence is too short. But the noise of approval is, this time, not a matter of course.

As they were setting up this afternoon cello player Muneer Abdul Fataah came and sat down next to us in the empty hall. "You know these people?" It took him a while to notice there was something unusual about the instrumentation. "It all looks and sounds perfectly natural, perfectly organic. Like they've always been up there." We let him in on the secret: most of these musicians are amateurs. In the best sense of the word. He just nodded approvingly.

Nobody Knows The Trouble I've Seen

Charles Gayle spent thirty years playing the streets for dimes. By the time his first record came out, all the masters of his school had either died or gone mainstream. Does that make him a traditionalist? An innovator? Neither really, unless that's what he was from the very beginning and no one ever got to hear it until now. He says he's been playing pretty much the same all along. He was the last musician to arrive tonight, he'll be the first to leave. Backstage he seems uneasy, solitary, intensely fragile, searching for something indeterminate that must be there somewhere, wafting around in the atmosphere.

When interviewers want to get him in his very best thunderstorm mood, they ask him whether he was influenced by free jazz. One look at him and you know: he is free jazz. Whatever comes or goes. To write a serious review you should know everything there is to know about what someone is trying to put together. Sometimes it hits you with the very first note. The message here is not that complicated. Charles Gayle has a soul, and we're allowed to witness it, but in the final analysis us spectators aren't really that necessary. He's all alone like God on Monday and that's the way he wants to keep it.

The promoter has been doing his homework. But so have we. So this is the accommodating approach, putting together musicians with roughly the same artistic agenda. You could do it the other way round too, pairing Martin with Charles and Han with Brandon. That would be going for the confrontational approach.

The sound mix is pretty awful. Maybe because Charles missed the sound check. Or maybe because Han is drumming even louder than he figured he would during the sound check. Han is home. "They look at me and they see a redneck", he asserted in the dressing room, sucking on a hash pipe long and thin as a drumstick. "That's why the black guys love to hear me play the way I do." Tonight he's the sole European performing with the founders and keepers of American classical music. Whipping the hide off the cattle, while the axe man roars out in the language of volcanoes, carves mountains, throws waterfalls and forests across them. In the meantime Muneer, the cellist, is bowing and plucking hard to be heard through all the driving energy of the horn and the absurd volume of the drums. Apparently he gets to solo when Charles needs to catch his breath. He plays his cello standing, like a bass player, the instrument propped up on a long metal peg and harnessed to his chest like a horn. Maybe he also plays the bass, we wondered out loud during the sound check? That turned out to be about the wrongest question you can ask any self-respecting jazz cellist. "No," he snapped, "I play cello. That's what I do."

Near the end of each of the two long improvisations the leader nudges the trio into one of those heavy vibrating spiritual fanfares we could swear we've heard before... Simple and powerful as a nursery rhyme. Them old masters would be proud to hear their estate in such honest and capable hands.

It Don't Mean A Place If It Ain't Got That Space

After all the negative buzz since the Arkestra arrived in Holland a few days ago, hardly anything could be disappointing anymore. This afternoon in the dressing room, a few of the Dutch musicians were mourning, in Dutch, the resilient ghost of the Sun Ra band. Many, like Han Bennink, heard them under the leadership of their founding father. "More than half are hired hands now," he sniffed. Therefore: not the real thing. Professional hacks, and not true believers devoted with every breath of their entire existence. That's a pretty mystical statement, coming from Han. Would he mind saying it again for Joe, who just walked in? But it was time for him to be needed somewhere else. "Ah, but I'm sure you'll love it, sweetheart," he laughed over his shoulder, and walked into the hall for his own sound check.

So maybe we should shun the gig altogether, and just sit it out backstage instead with all the grumpy old experts? No, fuck it, we'll make up our own minds.

Through the closed door in the back of the dressing room the chanting has already begun. In the hall the announcer is announcing the personnel is not quite the same as listed on the programme sheet, "in the great tradition of this band". Behind the horizon their song grows and then, voice by voice they step into the light, a glimmering ribbon rolling out towards the stage, and just as the last space cadet reaches his seat, at the flick of a wrist the whole band plunges into astro noise battle charge. Well-worn devices, sealed and predictable perhaps, and though we should know better we're enthralled, taken away and touched by a shadow of a spirit you never see on a stage, not now, not a thousand years ago either. This can only be Sun Ra's band. So that us poor slobs who only know it from records can get maybe just the tiniest glimpse of what once used to be. And so this bunch of castaways can pay next month's rent.

Marshall Allen. Photographer unknown.

Current bandleader is Marshall Allen, in service for something like forty-five years. A glance at the new CD tells us he writes most of the new material nowadays. The idiom is recognizably Solar. This band inherited one of the biggest, baddest band books in the big band business. They must have left it back home, unless another bunch of old guys claiming to be the Sun Ra Arkestra got hold of it first. Mainly straight swing tonight, spiced with just enough freakiness to turn off most square jazz fans. Some slow modal broodings too. Then another flick of the wrist battle cry splash into dirt trailing off in rare blood scream solo. And again way back home to the dance hall. Some new chants too. "Greetings from the twenty-first century!" A postcard from a world where every day is numbered.

Of course it's not the same thing. How could it be? Without the leader and most of the important players. Without the only man in the universe who could pull off those harmonies. Without the good master's whip to remind the soloists of their modest place in the greater cosmic order.

So once that has been established, maybe we can taste what's in that half-empty glass. A band haunted and sustained by the ghost of a music like nothing else in the universe. And at least one soloist like no one else in music. Marshall Allen, wide-eyed and jumpy, slaps the keys of his horn like he's throwing switches that stay put once hit, and that's the way they sound too. Then he unleashes his limbs on the Arkestra. Old Indian dancing for rain. Knowing he will succeed, once.

The timeless "Lights on a Satellite" strolls by, like a lazy dance for fat feet. After six songs the Arkestra sounds jaded, unfocused, the audience is drifting off, many have already left. And missed the best part. Chanting water, shiny rags, outer space in an atom. By the end of the song the audience at least sounds twice as big again. They exit chanting and marching through the audience. Of course. But leaving us wet-eyed and bewildered all the same.

Rummaging for more wine, we end up in the Arkestra's dressing room. Marshall Allen notices us examining a bottle of champagne and suggests we should open it. One of the band members starts to tackle it with a corkscrew. The others mock him mercilessly. There aren't enough glasses to go around so we end up sharing one with Marshall. We remember him from photographs. The hungry serenity of a chief disciple, so unlike us mortals who like the animals are still sound and not music. But in the flesh his eyes bulge and roll, he jerks and teeters with the controlled clumsy elegance of silent movies. Every bit an entertainer, from before the word was poisoned. And digging every second of it. Also very particular about his appearance. After hoisting on his long leather coat he goes on inspecting and ruffling it forever. "You look great, Marshall." His whole body responds with a big, aristocratic nod. "You're a great musician, Marshall. Just watching you perform is a treat."

A few last words with Noel Scott, one of the younger reedmen with the Arkestra. (If he had a straight job, he would have at least ten years to go before he could retire.)

"Rotterdam, huh? You got any good jazz clubs going nowadays? Ten years ago there used to be some good jazz clubs down there."

We suggest there's an interesting spot nowadays for, uhm, improvised music. Noel lowers his forehead, raises his eyebrows, frowns, grimaces, pulls a quick hard drag from his cigarette. All in one great dramatic gesture. "You mean that new shit?" Actually, no, we meant that European shit, but it's hard to reason so sharp when we're feeling like schoolchildren caught with comic books under our desks.

"Aw man, I'll tell you one thing I'm a bebop man... I mean here I do all kinds of shit but with my other band, which is my own thing, what we're doing is upholding the tradition... remember, it don't mean a thing if it ain't got that swing..."

Well, okay, I mean there's no challenging a quote like that in company like this... but still, aren't there lots of other ways you can swing? Or has this really been a straight jazz band all along?

"Yeah sure man, but I'm talkin' about that swing, you get it, it don't mean a thing if it ain't got that swing... Sure there are other... uh, things... but that's not jazz... It's that vibration, you just know it when you hear it, and it makes you want to get up: hey, so that's what they've been talkin' about!"

All words and images copyright 2001 by Vanita & Johanna Monk.

R:IP photos by Jacek Futiakiewicz. Raffinaderij photo by Katja Vetter.