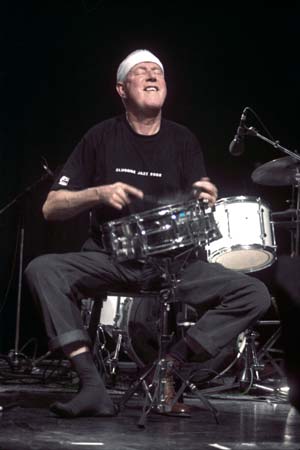

Han Bennink. (More photos...)

Music Unlimited XVI

Wels, Austria, November 8-9-10, 2002.

A weekend in an Austrian slaughteryard with John Butcher, Peter Brötzmann, Beñat Achiary, Han Bennink, Hamid Drake, Sylvie Courvoisier, William Parker, Michael Zerang, Fred Lonberg-Holm, Kent Kessler, Otomo Yoshihide, Yamatsuka Eye, Silent Block, Ken Vandermark, Terrie Ex, Andy Moor, Konrad Bauer, Mats Gustafsson, Ikue Mori, DJ Olive and Dälek.

When we listen we are the silence where music writes itself. Black paper where the notes of light appear. Without us there can be no music. Without us to hear it sound remains sound and flows away unheard into the stone of the earth.

The world's libraries are overstuffed with the yellowing immortality of published writers echoing ME Me me fainter and fainter until they're broomed offstage to make room for a new generation of immortals. Even the chosen few who remain in the collective mind long enough for a reprint in the "Classics" series, never live to enjoy their posthumous success.

Kafka wrote to break through the membrane of routine, to hear the electricity living in the bowels of the earth. Van Gogh didn't paint to fill up the Van Gogh Museum with shrewd investments but to dust off the sun every day again. To remember that it's a living coil of fire, and not just a light bulb screwed in the cosmic ceiling to accommodate the human grind.

Charlie Parker got thrown out of his own nightclub, but now right here on the waterfront boulevard in Rotterdam they have an "easy listening jazz lounge" called Bird. The only instruments in the place are on the walls. Underneath the boulevard, in a dusty rehearsal vault, what's left of the legendary Jazz Bunker, we meet irregularly with the local crickets and make noise and songs the world above the ground doesn't want to hear.

We write, not to be remembered, but to remember. We write about a music that can not be duplicated. About artists that refuse to be replicas. It's hard enough to remain alive among the walking dead. The world is ruled by machines. They work like machines and play like machines and march to war and march for peace like machines, love and hate like machines and spawn little machines, satisfied, terrified machines. Improvisation is strong medicine against the mechanization of humanity. A single sound can disrupt the machinery. Punch a hole in the forgery.

Festivals come in two flavors. The first kind exists mainly for the benefit of the organizers, who climb into the spotlight before and after each concert to remind everyone how amazingly fantastic they are to have organized something so fantastically amazing. Military rule applies throughout. The commanding officers personally roll back anyone who dares to challenge their absolute sovereignty over the musicians, staff, environment, and whatever else they feel they must defend. The musicians are shielded from the "crowd" by stockades of spotlights, walls and doors, escorts and sentries, and a lobby designed for minimum communication and maximum profit. The audience is treated as prisoners of war: humanely, as long as they behave themselves. Tickets, drinks, seating and applause are all mandatory, everything else is prohibited. The audience serves an essentially statistical purpose. Enough to generate the campaign funds needed for another term in power? Enough to get the corporal promoted to sergeant?

Peter Brötzmann & Mats Gustafsson. (More photos...)

Music Unlimited (now in its sixteenth year) is one of those places and times few and far between where refugees, deserters and other cultural noncombatants get together for a weekend of fierce but unarmed resistance. "Wolfgang," apparently the main ringleader, found our web site and mailed us asking if we could make some kind of announcement "if you think the festival and its program is any good". Modesty and a sense of understatement are not usually the most obvious qualities in this line of business. In this case "the festival and its program" sang its own praises.

Halfway across Europe on the Cologne-Vienna express. To the cuckoo-clock-clean town of Wels, Austria (the country of Wittgenstein, Schönberg, Mozart, Freud and a few other characters they're not quite so proud of). Streets so spick and span we began to suspect the rain here comes down complete with soap. Gusts of autumn wind looking in vain for a bit of stray litter to dance with.

But Wels is also Austria's little Chicago, another town with a history of bad blood and good music. We quote from a brochure praising the town's main annual event: "Austria's largest industry fair on the topic of meat offers a venue for all partners of meat for subsistence and delicacies. From breeding and processing machinery all the way to the finished product, the entire meat industry is represented here. The location of Wels, in conjunction with the ÖFFA Meat Forum 2002, is to function as a focal point for the meat industry and its partners..."

The home of the Music Unlimited festival is the Alter Schlachthof (Old Slaughteryard) where all magical and alchemical cultural practices converge all year round and climax in one hot November weekend of free music in the freest sense of the word. Years of creative resonance and the highest concentration of vegetarians per square meter in Upper Austria have reclaimed the Slaughteryard from the rusty smell of blood and history. The echoes of nameless animals prodded with electric poles into one side of the factory and rolling out the other side in little tin coffins. The label shows a pig cheerfully sticking a knife and fork in his own ass. There's nothing he wants so bad as to be eaten up by you, because you're such a unique human being, just like everyone that bought the same happy product. Advertising people have peculiar ideas about what constitutes happiness. And for whom. Like all cynical idealists, they become really dangerous only when too many people start buying their myths.

We would have a hard time putting in words how much the festival and its people took us into their hearts and their slaughterhouse. Lucky for us the ethics of journalism forbid us from doing so.

We catch up with some old friends (Hamid Drake vows that we're finally going to lay down that interview we've been stalking him about for a year) and make some new ones. And drink way too much Austrian wine until we pass out in the rehearsal booths downstairs with a couple of the local hip-hop kids who also haunt the obsolete death rows of the Alter Schlachthof.

John Butcher (saxophone) blows the first note of the festival, a twenty minute note, a note like the surface of a sphere, finite and yet unlimited. Science is magic, freedom is mathematics. Freedom to set up your own iron rules, and then break them, with the same precision, the same love and logic you put into setting them up. Daily life confuses science with technology. Music, like true science, isn't about finding convenient answers. It's about finding inconvenient questions. John spent the better part of the afternoon trying out reeds and warming up horns ("I can go on doing this for days"). Did he find the sound he was looking for? Was he looking for any particular sound? For that one sound out of an infinity of sounds, existing in the same time and space, existing only because he and we are listening? It's hard to imagine this quiet Englishman could be capable, even in the privacy of his own soul, of anything as violent or vulgar as an emotion. Like John Cage, he has nothing to say and he is saying it, the sound of one horn slapping, tapping, rapping at our chamber door, leaving our minds sounding as clear as his, forever more.

Hunting for Dictaphone tape... The town quickly closing down for the weekend... Our last chance, the one store in town that carries what we need... Closed, geschlossen... But sympathetic to our knocking and begging through the glass door.

"You here for the festival?" the owner guesses. Turns out to be (small town) one of the founders of the Music Unlimited festival. Used to collect drumsticks Han Bennink had broken. Thinks he's "too old now for all that kind of noise," so he hasn't been around to the Alter Schlachthof for years. "Han is older than you," we tease him, "And he's playing there tomorrow". The next evening at the festival we spot the man having a beer with our host Wolfgang. He waves at us and we see Wolfgang wondering how these people could possibly know each other. Or maybe not. Small town after all.

Peter Brötzmann. (More photos...)

Peter Brötzmann (saxophones, tarogato), Konrad Bauer (trombone), Mats Gustafsson (saxophones), William Parker (bass), Hamid Drake (drums). Flight of wild honks and chirps moving south before the big chill sets in. The ground answers, cries back, rises up to merge with the trek. Everything that can fly is welcome. Alarm birds, guard birds. A vaccination against violence. The leader of the flight moves back, out of the light, closes his eyes, his silence as musical as his playing, to leave some oxygen (rare at such altitudes) for his flying companions. Dark bass, black thunder on horizon, silent as living stone. Forever standing, breathing monument, tower stretched tight like a bass string. There's no such thing as gravity in his Tone World.

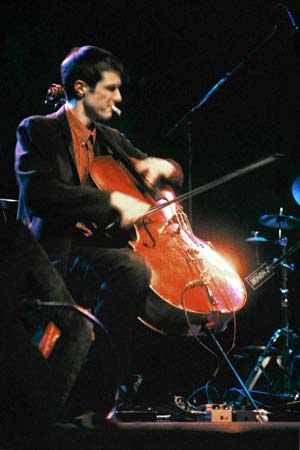

Fred Lonberg-Holm. (More photos...)

Fred Lonberg-Holm plugs in, lights up and chain smokes a pack of electric cellos. Michael Zerang focuses 2000 centuries of music and dance into a little point in time and space sharp as a single drum stroke. Kent Kessler grabs his wild bull fiddle by the horns and rides it until it comes singing back home.

Otomo Yoshihide makes a stack of bad records sound good again by ruining them. Yamatsuka Eye howls through an oversized funnel, spine arched back reaching deep down wolf pack reunited.

Silent Block (Xavier Charles, Jérôme Jeanmart, Stéphane Levigneront, Frédéric Le Junter) make music out of everything but music. So much to see and too much to hear with open eyes.

Sylvie Courvoisier (grand piano) has the 19th century romantic tradition sampled and sequenced in the wires of her hands and brain. A tradition where "pianists" still improvised. Ikue Mori (electronics) and DJ Olive (turntables) meet her in the time chamber. "Was it that obvious?" Sylvie asks when we praise her mastery of the masters. Let it be obvious, we say. Let the music eat and grow and spawn and die and be reborn. As Peter Kowald said, this is a truly global music we're creating. This is not the idiot bastard son of jazz.

One of the kids we got drunk with in the basement thinks we should interview Dälek, his heroes and role models, a mutated hip-hop crew from the radioactive suburban swamps of New Jersey. No use explaining we wouldn't have any idea what to ask these guys. Little did we know.

The foundations of hip-hop suggest a low and heavy ceiling. More a bomb shelter than a home. Sunny skies as remote as the galaxies. As good a place as any to set out on the quest for freedom. From the dead end streets of race and rage. The ghettos of local and global folklore. A working class hero is something to be. Courage is the total realization that there's only one way out. These brave souls didn't choose hip-hop. They were drafted. We offer them a magazine and find out they know a lot more about our music than we do about theirs.

MC Dälek (words, vocals, black box, twisted beats only he can rap to, lamb of god), the Oktopus (buttons and knobs, frowns, lurking in the shadow), DJ Still (turntables, including screaming into and allegedly engaging in lewd and lascivious acts with the pick-up needles, no prior arrests). First the hip-hop venues wouldn't have them because they were too avant-garde. Then the avant-garde venues wouldn't have them because they were too hip-hop. Now they're playing and recording with bands like Zu and Faust. And yes, they improvise. Just don't ask us how.

So we went. And we saw. And we heard. And then we wrote a little rap of our own. Protest, praise or parody? Check it out!

Who rules, who is ruled, who's the mob and who's the tyranny?

What's wrong with life under the ground, death in obscurity?

Got a mind, got to take out the slime

Whose rhyme is an ode to a crime, a stuttering pantomime

A public enemy in apathy, atrophy

The poor man's hungry hate is his soliloquy.

Me and my twin blood brothers, attitude and skills

Made a killing at the mall, now it's time to collect the bills

Exterminate the competition with a hail of sleeping pills

Show some respect for my product, my weapon and my error

The dirty words of hate and terror, the chains too thick to sever

The gold that keeps the slaves starved and shackled down forever.

Did I say something wrong, did I miss the point?

I got a hundred years in jail for passing a joint

Distant crimes of war come as no surprise

With all bullets and the bitches that we fantasize

We got the leaders we deserve, gangsters to protect and serve

All our wars and institutions stick to the population curve

I turned the switch, nothing happened, and now I'm mad

The pump don't work 'cause the jihad spread to Stalingrad

I'm gonna bring down the system, gonna milk my goat

Scratch my records unplugged, ain't gonna shop or vote...

Having curated last years Music Unlimited, the Ex are everyone's favorite band in Wels. Rumors that they might be breaking up, plus the mysterious presence this year of the band's two guitarists (in the ad hoc power quartet Skins & Strings with drummers Han Bennink and Hamid Drake) have the Slaughteryard buzzing with confusion. Fans getting ready to throw themselves under Terrie and Andy's guitars.

Hamid Drake & Han Bennink. (More photos...)

Han spots us backstage after the sound check and summons us to the quartet's table: "Hey, my friends from Holland!" Our quest for an interview with Hamid can wait another year. We put away the tape recorder and have a glass of wine. Han's pipe smells good. "You sure you can miss some, Han? With all the borders you have to cross?" Han just laughs and mimics the way Gil Evans used to stroll through customs, the cops kicking the weed-sniffing dogs off of him. Because he was Gil Evans, a natural born gentleman, always slipping through the unspoken cracks in the fabric of time-space. And the time Louis Armstrong got Nixon to carry a trumpet case full of marijuana into the Soviet Union... (and I say to myself, what a wonderful world!) One of the natives obviously familiar with Han's tastes comes in and offers him a bag of weed big enough to get him all the way to Vladivostok and back.

After two hours of talk and wine and smoke, Han looks at the clock, claps and rubs his hands: "Right! And now for some strong coffee!" Two hours of methodical chemical buildup. By the time he hits the stage "I don't have to worry about how to get started, the limbs just go off by themselves!"

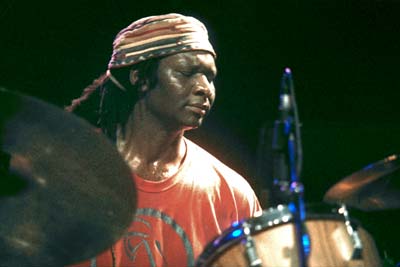

Hamid Drake. (More photos...)

Not everyone can indulge with such discipline. Or such practicality. Hamid remembers touring through Africa with Don Cherry and Charlie Haden, watching them try to cop for junk in every town they played. Everybody loved Don. Everybody got hurt. Best detox for junkie romanticism: listen to the life of a great artist on junk, as seen through the eyes and heart of a great artist not on junk.

Hamid also remembers a record called Orient that Don made with Han in the early seventies (got to get that record): "Man, that was like the Bible for us." Han, who must be accustomed to compliments after four decades on top of the world of jazz, free jazz, free music and just pure music, glows like he's been handed the only one award that still means anything at this point.

Han Bennink is the musicians' revenge on the industry. Makes every sound engineer sound like a bumbling amateur. Best solution would be to keep the mics as far away as possible from those sticks of mass destruction. But tonight even Han needs an amp, with Ex (or ex-Ex?) guitarists Terrie and Andy banging and scraping their electric tendrils against the floors and the stage installation (tar and feathers fluttering off with each attack). Ken Vandermark makes a brief guest appearance and actually manages to get heard (a truly heroic moment) through all the density and the gigabels.

And Hamid back on the evening shift, tireless even after last night's power flight with the Brötzmann group and subsequent all-night drinking and dancing until we walked him back to his hotel room at 7 AM... and still no interview. Hamid is the human totem pole of seven continents. The drummer with a little bit of every drummer in the world inside him. The wild man and the seer. And sometimes just the "plain old" drummer. He doesn't need frame drums, bells, tablas or a beard to make great music. One day we might even see him playing with his shoes on.

But it's Han Bennink, by far the oldest of these four noisy gentlemen, who's left standing alone onstage after the set and the encore, the audience screaming for more, Han screaming for more, glaring into the wings, pointing fiercely at the stage floor. Hamid joins him for a second encore while the guitarists watch on in admiration.

Beñat Achiary. (More photos...)

Beñat Achiary slips in without disturbing a single air molecule in the room. We offer him our magazine: "Here, on page three, Peter Kowald's last in-depth interview. He's the one who told us about you. Right here. So when we heard you would be doing something for him tonight... Maybe this is not a good thing to say just before the concert... But for us Peter was... Uh..."

"A great friend." Not a question. Achiary communicates in short, finely tuned signals. His voice too valuable to be wasted on small talk. His ears recoiling visibly at each word that is not absolutely necessary. We leave him with the magazine. Find him later on all alone in a small quiet room on the way to the toilets. Doing nothing. Looking up when someone walks in. Smiling when smiled at. Saying nothing. Saving his voice, his words, his presence for the stage.

It was supposed to be a duet with Peter Kowald. Peter died so Beñat has to play and sing for both of them. Not a tribute but a duet with the other side. Ghost arm breathe in and out. Grind roar cry. Boom sing gurgle. Throat ride on the back of a bass bow.

The festival ends with the bar staff tapping and pouring to the rhythms DJ Olive is pumping out of a string of briefcases. Until the November sunrise, for the third night in a row. So now we know why they call it Music Unlimited. Just before he leaves we offer Olive a magazine: "This is the last copy, we'd like you to have it." Barely glancing up from a fistful of wires, he snatches it: "Yeah, I got one of those. I'll take another one." You're welcome, Olive. And thank you too.

Find out more about the Music Unlimited Festival at

www.musicunlimited.at

(opens in a new tab or window)

All words and images copyright 2003 by Vanita & Johanna Monk