WAR?

What's America afraid of?

Deaths on US soil in 2001:

weapons of mass destruction - 0

international terrorism - 3,019

firearms - 11,127

traffic accidents - 42,556

In the October 2001 edition of Oxford American magazine, amateur saxophonist Bill Clinton was asked: What would people be surprised to know that you listen to? The retired statesman's answer: Brötzmann, the tenor sax player, one of the best alive. It wasn't all that hard to imagine "Machine Gun" booming through the West Wing, perhaps during the dark days of impeachment (and collateral bombing of the dark side of the Earth). As we watch the newly appointed administration gearing up to defend our Way of Life, we shudder at the thought of what strange sounds now make the Chief Executive Big Toe wiggle. Something God-fearing no doubt... Charles Gayle? Guess not. A violent society might need violent music, that doesn't necessarily mean it wants it.

Somewhere in this magazine Alan Silva says that war doesn't stand a chance when people are listening to music instead, when young people want to make music instead of going off to war. It's hard to disagree. For another perspective though, ask Europe's Gypsies how useful their music was in the face of bad taste with marching orders and a license to kill. Ask the musicians in Iran and Afghanistan whose instruments were burned, who were beaten with their own instruments. When Gandhi was asked if non-violent civil disobedience would be effective against something like Hitler, he was quiet for a while, then answered: "Not without much, very much suffering". Are we sincerely ready to be on the business end of all that suffering? Peace is a luxury not everyone can afford. When does the musician become a warrior? When he has nobody left to play with because all his friends' hands have been chopped off? Music is a force too powerful to waste on consolation. Music can mobilize us, music can offer a real alternative to war, an alternative to turning the other cheek, an alternative to the food chain of greed and terror and cynicism. It already has.

Stockhausen, gone too far? He's done much worse: he's demonstrated poor taste. Art is creation, not hate-soaked vandalism. As an art performance, this atrocity had nothing going for it but volume and shock. The humanity of the victims is what makes drama compelling, not the ingenuity of the murderers, or the budget of the special effects department. Destruction is the oldest trick in the book - great impact for a fraction of the cost and effort. The last resort of the uninspired. Epater le bourgeois. We were once the unwitting victims of this sort of "radical" attention-grabbing tactics. Something like an acoustic version of the nerve gas attack on the Tokyo subway. The secret weapon: a barrage of digital noise at extreme high volume and extreme high pitch - barely audible, and thus insidiously potent. The terrorist: a Japanese (of course) noise "musician" who shall remain unnamed, for the sake of world peace. The effect: a painful over-sensitivity to high tones that ruined many a musical experience for the next few months. Is this art?

Most of us prefer to create. Music. Skyscrapers. Whatever. We might differ on what exactly constitutes creation. We might feel untouched when 5,000 squares go up in smoke ("real people" never go down there, and anyway those soldiers of capitalism had it coming). We might calculate that the current mayhem will slow down global burnout for a few years. But when "folks" with an agenda to crush everything they can't control start to decimate our audiences, dictate how and when to make music, then outlaw anything that doesn't fit into their narrow illusions of perfection... before you know it you're the terrorist. Guilty of not knowing your place in line as a consumer of pre-processed culture. Guilty of expressing an idea you came up with yourself. Guilty of a peaceful exchange of ideas between friends over a bottle of wine. It's time for a new kind of war. This time, let's not leave it all up to the squares in the towers and the pentagon to decide the terms.

Strict pacifism means leaving your door unlocked, and not defending yourself or phoning the cops when the thugs (victims of this heartless society) walk in to smash your records and burn your books, rape your loved ones, and slit your children's throats. Non-violence, like terrorism, relies on manipulation of your enemies' emotions. They are both quite ineffective against a perfectly ruthless opponent.

***

In the best of all possible worlds there's a hangout for unusual music. Hang out long enough and you're part of it. Some come for the music. For a few years we (the Board of Editors) camped on the front row. The whole organization, the few professionals, the immeasurable herd of volunteers, revolved around us. Us, and the few other paying guests. For the price of 2-3 Big Macs, or 2-3 sax reeds, depending on the way you consider the cost of living. Even the tickets were little miniature works of art.

Music created smashing resurrection of sound right in our face. Lifetimes of study and practice, of dragging equipment up and down continents. For our ears only. And thanking us afterwards, for listening so well. The kings of lore were paupers compared to us. Always that same minstrel with his same three fucking chords. Vaults full of gold and not a record store in the world.

This is where the R:IP and us met and touched. In the space where their golden and leaden moments met and touched. The R:IP, for those among our esteemed international readership who don't know them yet, is Rotterdam's ongoing co-operative improvisation workshop, a hotbed of local talent that's been holding on for 11 years now. They invited us to tour with them and to write for their bulletin. A year later the piece we submitted is still not published. The editor's chair is growing cobwebs. So now the listeners are going to say something for a change.

In these years of listening and playing we sprouted a few questions. Our modest aim: to initiate a fundamental dialogue about improvised music. Nods of approval. The first response is by AMM percussionist Eddie Prévost. Who of course has a lot more time to consider a few questions for a local amateur magazine than the local amateurs themselves. Peter Kowald, stopping in Rotterdam just long enough to perform two unforgettable sets, hears something about a pageful of prickly questions we've been fine-tuning, and demands to see them. He assures us we're doing the right thing at the right time. The music wants words, a voice. On both sides of the stage, young musicians, new audiences, loving what they hear and wanting to understand why.

Free music isn't dead. But there's a price on its head.

All things must pass. For a while now the clubhouse doesn't want to be a clubhouse anymore but serious, like a real modern temple of culture. Dodorama - a name pregnant with extinction and death, just like R:IP, has gone down under and been digested by a new organism named Worm, which again brings to mind the consequences of passing away. Everybody's happy except the mumbling malcontents and they don't make much noise anyhow. If you don't like it you can always stay home. We still show up for the good concerts but leave before the nightly bingeing and senseless fun don't happen anymore.

There are more than enough lovers of good music in this town. Anyone ever asked someone why no one ever comes to a concert anymore - and got a straight answer? In this year when Rotterdam has been thumping (and digging into) its chest as the Cultural Capital of Europe, culture here and now equals entertainment and social work and not much more. Outsiders, used to more cut-throat cultural politics, might drool at the public udder creative artists can suck on here. But milk is for babies. Milk is laced with substances devised to keep babies quiet. All this so-called support makes us weak. Drains our energy. Keeps us on our knees and focused on the wrong things. So we go on scrambling for the loot, elbowing each other in the eye to get a bigger gulp of the swill. And tailoring our art, be it ever so subtly, to meet the requirements of the cash-generating machine. Tolerance is repression. "A functioning police state needs no police." (William Burroughs). Our modest proposal (for preventing musicians from being aburden to their parents or country, and for making them beneficial to the public): Stop all subsidizing. Pull the plug. Just for a year. See what happens. Who jumps ship, and who endures.

So we were on our way out. Others had already left. Then the Last of the Mohicans threw an axe at our feet. A call to arms. Walking out is cheap. Why don't you feed what you love? He thinks all is not yet lost. He's been beating his drum in other quarters too. Music that means something should be crawling with grubs that digest it and fly out to lay their infectious eggs everywhere. The R:IP has already spawned the V:IP - a monthly evening of take-no-prisoners improvisation sessions where local multi-instrumentalist Hugo van Rooij combines, manipulates and abuses musicians like he would a set of drum heads or piano keys. Oases of electricity in a year of tension mostly wasted on much more trivial pursuits.

Words and music. And never the twain shall meet. Soon you catch yourself listening to yourself more than to the music. If you're successful, you become something musicians fear or loathe, or with the wisdom of years, learn to ignore. But they still need the plug. You become the straight guy. The man. Swimming at the bottom of the same barrel as club owners and record producers and festival promoters. You become another commodity in the entertainment business. At least the artists have their art. What does the critic have? Some players say there's nothing like a fight with the promoter just before the gig to build up tension. Does music sound different when you're subsidized to do it, as opposed to risking jail? That should be the subject of a new blindfold test: the naked ear. We will not inform consumers. We will not pretend to know.

We've been asking a lot of questions lately. The toughest questions we kept for ourselves. The questions no master should answer. We can easily exploit the given freedom. Can we also create new freedom? Or are we just filling in the holes? The parameters of free improvisation are comfortably close to becoming established, formalized, a "genre". We're already looking back at a Golden Age of free music. Leo Records has a "Golden Years of New Jazz" series out now. We're waiting for a Hall of Fame. We know how much later than announced the concert will begin, what the players will sound like. What's it gonna be tonight, a single one-hour set, or two sets of 45 minutes? We know when to applaud. Do we come to hear "the sound of surprise", to learn, to analyze, to compare, to be entertained, to be moved, to see if they can pull it off this time again, to meet people? Can we really blame those who stay at home watching TV?

Fed up with the local scene (someone here has been giving good music a bad name) we took a trip down south for Antwerp's 28th Free Music Festival. Antwerp and Rotterdam are about the same size and both cities share a history of docks, workers, poverty... and jazz.

In Antwerp every year 200 music lovers pack a theatre for a couple of days of mostly world-class concerts. Funding is of course of the barrel-scraping variety. Fred van Hove, who with a handful of friends has been pulling this precious little festival through some very lean times, tells us the money to pay the musicians isn't nailed down until sometimes just a few days before the festival.

In Rotterdam, that would probably be enough to get you blacklisted as a promoter. Of course Fred is more than just a promoter.

In Antwerp, free music hideouts pop up every month in private houses and garages and relocate again when the neighbors complain about the noise. The fans keep each other informed by word of mouth.

In Rotterdam, for a typical concert of free music, we're happy if the number of paying customers exceeds the number of musicians onstage plus the number of subsidized volunteers in the back.

In Antwerp, we could hear the solo trombone of Johannes Bauer, recorded just a few hours earlier in the church, blasting through the red-light streets - from a radio in a snack bar.

Someone here has been giving free music a good name.

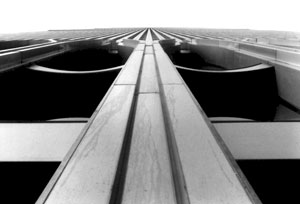

Monastery photo gallery:

All words and images copyright 2001 by Vanita & Johanna Monk

except WTC aftermath photo by Associated Press.